It’s Opening Day today – the fifth I will attend in person, but there have been so many more. They have been special and full of hope, dreary and full of foreboding, and everything in between since I started paying attention to them. I don’t remember exactly when that was, only that it’s been around thirty years.

Dad and I only went to one Giants game together, although he did take me to a Sacramento Solons game in the mid-seventies. The Solons were the PCL team in Sacramento (somehow they were the Milwaukee Brewers AAA affiliate, although I had to look that up on Wikipedia just now) and I did not care about them at all, and I suspect Dad didn’t really either. The only thing I remember about the game was that Dad had given me a silver half-dollar – both an enormous amount of money to me and – given my size – also an enormous object – to buy a snack with, and I dropped it and had to listen to it roll away down the slope of the stands. It was a tragedy, as I’m sure the entire game was. The Solons were not a hugely successful team.

Anyway. I wrote this piece the year after Dad died. It was published, much edited, in the San Francisco Chronicle on April 12, 2012, but I think this is a better version.

When I was a kid, in the late ’60s and early ’70s, my dad was a Giants fan, and I had no idea what that meant; he sat with the lights out in our living room in the summers and listened to the Giants on the radio. He called them “them pesky Giants.” It meant nothing to me; I played with trucks and blocks and heard the words on the radio but didn’t listen. He didn’t live and die with the team’s fortunes; he wasn’t that kind of fan. He loved them, though, and the 49ers, who he watched on television. In the ’80s, his devotion to the Niners paid off, with Montana and Taylor and Craig and Rice and then Young coming through for him in that exuberant decade and a half, but his loyalty to the Giants wouldn’t be so richly rewarded for another fifteen years or so.

By the mid-eighties, though, I’d moved out, and no longer sat at his feet in the summer shade with the Giants struggling along. In 1989, when the A’s and the earthquake slapped San Francisco around, I was living on my own, seeing my father every couple of weeks or so, and baseball wasn’t part of my world at all. I have no idea how he felt about the sweep – no, I have an idea, but we didn’t talk about it. I didn’t care about the game at all, didn’t know about Roger Craig or Hum Baby, Kevin Mitchell or Will Clark, and he never mentioned any of them; the pesky Giants of my childhood were still a cipher, but only because I didn’t care. I was a teenager and didn’t pay much attention to my dad or his teams.

In the ’90s, I moved to the Bay Area and discovered, accidentally, that I was a baseball man and a Giants fan. A nighttime driving job with nothing but an AM radio left me with the Giants, Rush Limbaugh, and mariachi music as my only choices for entertainment on the road, and the darkness and the silence and the radio brought back those peaceful days at his feet in the summer dusk of our darkened living room. Behind the wheel of a delivery truck, I was a boy again – the age when baseball is supposed to be woven into your soul – and the seeds my dad had sown flourished and flowered. His pesky Giants became mine, and all of a sudden I knew what he knew.

For the next twenty years, my dad and I always had something to talk about. I became, much to the surprise of my family and friends, a baseball fan. Lon Simmons and Jon Miller were my companions most summer nights from then on, along with the players and characters they brought so vividly to life, and whenever I went back home, even in winter, they were a bridge between me and my dad. We sat in his new house and watched the Giants play; I asked him questions about strategy and tactics and rules and why didn’t they do this or whether that would work. I was surprised to learn that sometimes he didn’t know things. As a child, I thought he knew everything; in my twenties, I came to respect him the way Mark Twain said I would, and in my thirties I found him to be human and fallible – a man like myself, in a way I had never suspected.

We had sometimes failed to connect as people, as fathers and sons sometimes fail, but the bridge was there, and we could meet on it and stand there while we learned other things about each other.

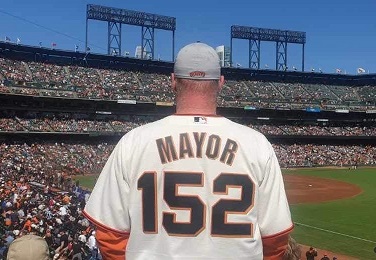

One of the things we learned, in 2004, was that he had multiple myeloma, a cancer of the blood. We talked about it on the way to a ballgame at what was then SBC Park, a game we watched from the Chronicle’s season ticket seats – a gift from my cousin Christian Berthelsen, a Chronicle reporter at the time. Dad told me that he was at peace, happy with his life, that if the cancer killed him right then he would feel that he had lived well. A couple of hours later, a foul ball missed his head by a foot or so. We joked that he didn’t need to worry about cancer if he was going to live so dangerously, and I got the foul ball and gave it to him. The next time I went to his house, it was in a Lucite box hanging in his hallway, under a framed painting of a baseball, and it hangs there still.

The cancer was more or less a death sentence, and it got him eventually, but a series of treatments, often miraculous, often harrowing, kept him going for seven years. Doctors, family, and will kept him alive until April of 2011, when the cancer took a radical turn for the worse. We joked sometimes that he had simply refused to die until he saw the Giants win a World Series. When they brought the trophy home in 2010, we celebrated together with a joy that reflected all the sweetness and innocence of the bond between a father and his child and all the ready heartiness of a triumph shared by equals.

From the first of April, when he walked into a Kaiser Permanente office and told them that he wanted to cease the treatments, until the tenth, when he died, I was with him every day. His decline was rapid, the way he wanted it to be; he was essentially in a coma by the eighth – a win over the Cardinals was the last game he really comprehended – but every day before that, he asked me, with decreasing lucidity, when the game was on. Sometimes, in the last couple of days, he asked two or three times, forgetting that he had asked already, or that there was no game that day. He couldn’t see the TV, but we still put it on, even after his eyes had closed for the last time. On the ninth, I sat by his bed and held his hand while he slept and told him – the nurse said maybe he could hear, even though he couldn’t respond – about another win. The sounds of the Giants, the music of Johann Sebastian Bach, and the voices of his family were the things he heard in the last two days of his life.

This will be the first Opening Day in close to twenty years that I won’t be talking with him about the Giants and their fortunes, or sitting with him on his couch, in his living room with the lights out, cheating the summer sun in Sacramento. Today, though, and every Opening Day from now until I join him, I’ll have my dad’s shade and the radio and the memory of summers to keep me company while I listen to the Giants. Win or lose, they’re my team, a vital part of my inheritance, and even though my dad is gone, I will always think of turning to him to cheer for a hit, calling him to talk about pitching, and hearing him say, on so many summer days, “How about them pesky Giants?”

One response to “The 1970s, the 1990s, and 2011: Dad”

That is beautiful, Justin, touching on so many levels. For me, it brought memories of seeing my own dad pitch in our little small town, while we kids watched a little, but mostly played. Then memories of Elmo teaching Kevin to pitch, the years of little league, and all. Memories too numerous for this space, but most of all, a glimpse of a special father son relationship between two of my favorite men.

LikeLike